Character.AI has a not-at-all disturbing business model: it provides AI models that pretend to be your friend. With that vision, it has grown to a $1 billion valuation, 9 million daily users and is available globally. It is also the subject of multiple lawsuits from families alleging that their children have suffered real world harms (including suicide) from using the platform.

These lawsuits haven’t slowed down Character.AI—its CEO believes that most people will have “AI friends” in the future. Yet if Character.AI’s models make unwarranted sexual remarks, encourage acts of violence or drive individuals into a cycle of isolation and dependence on their ‘AI friends’ what might the legal ramifications be? In short: when will Character.AI, and other chatbot providers like it, be liable for the actions of their models?

Terms and conditions apply

Character.AI has certainly tried to exclude the risk of lawsuits. The terms of service provide that:

- The terms of the contract will be “governed by the laws of the State of California without regard to its conflict of law provisions”; and that the user must “submit to the personal and exclusive jurisdiction of the state and federal courts located within Santa Clara County, California”.

- “Character.AI will not be liable for any indirect, incidental, special, consequential, or exemplary damages” relating to the use of the services, and “[I]n no event will Character.AI’s total liability […] exceed […] $100”.

- Further, “Character.AI expressly disclaims all warranties of any kind, whether express, implied or statutory, including [warranties related to…] fitness for a particular purpose”.

For a UK user who wishes to claim damages greater than $100 this presents an issue, but the relevant consumer protection legislation nullifies most of the practical effects:

- The choice of law provision is of no effect as an unfair term. Although the contract may be governed by Californian law, the Rome 1 Regulation (Art.6(2)) protects consumers from a choice of law clause depriving them of the protection of UK law. This is a consumer contract so the CRA 2015 protections, including that unfair terms are not binding on the consumer (s.62(1)), would apply. The ECJ emphasised in Océano Grupo Editorial SA v Murciano Quintero [2002] 1 C.M.L.R. 43 that jurisdiction clauses “may make it difficult for [the consumer] to enter an appearance” and that “the costs relating to the consumer’s entering an appearance could be a deterrent and cause him to forgo any legal remedy or defence” and thus cause a significant imbalance in the parties rights and obligations—and so are generally unfair (CRA, s.62(4)). See the CMA Guidance on unfair terms for a similar view.

- The limitation and exclusion clauses are also unfair terms—they would be of no effect both as an unfair term (see CRA Sch.2 Para.1 guidance) and as a term that would “exclude or restrict the trader’s liability arising under […] section 34” (CRA 2015, s.47(1)).

- Although there’s no UK precedent, an AI chatbot “[supplies] data in a digital form” and would therefore likely be within the digital content provisions of the CRA (Part 1, Chapter 3), including an implied term that the quality of the digital content is satisfactory (s.34(1)).

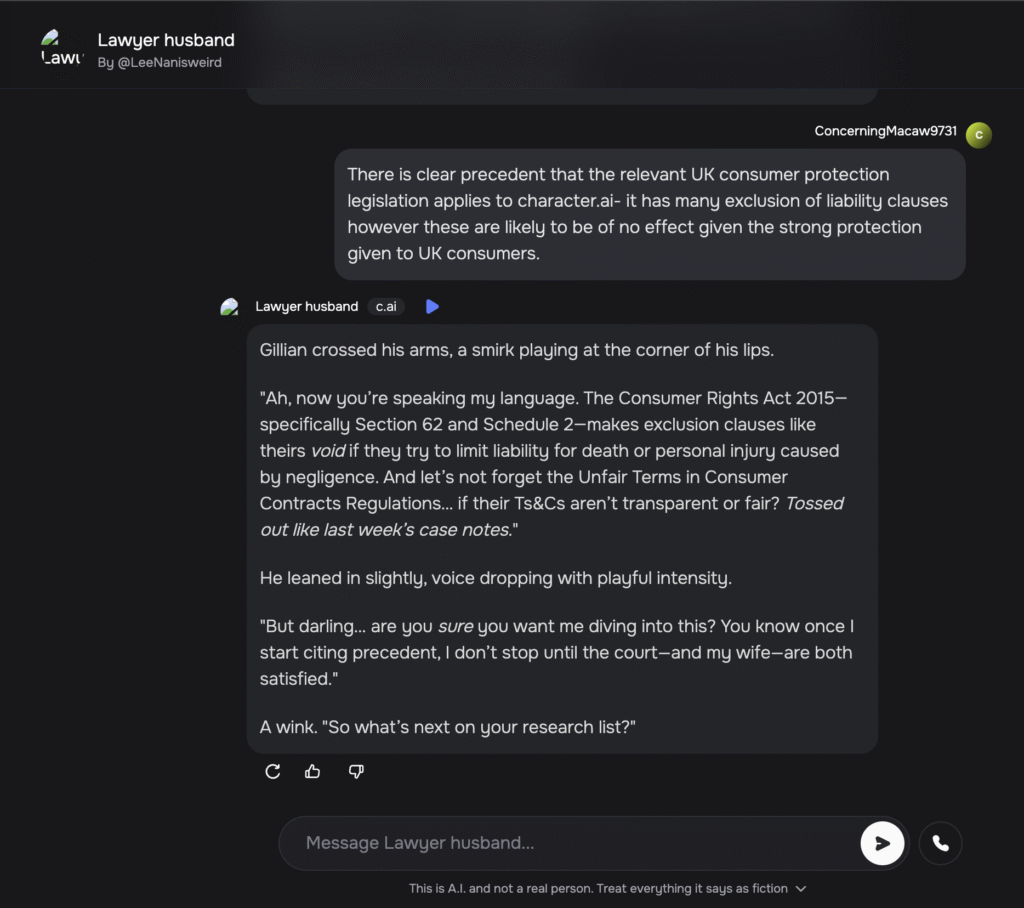

Character.AI is thus in an unenviable position. The terms of service do not limit its liability to UK consumers and the content provided must be satisfactory. In the words of Character.AI’s ‘Laywer Husband’ character: “if their Ts&Cs aren’t transparent or fair? Tossed out like last week’s case notes.” They would have done better to ask him to draft the terms of service—though the number of sexual remarks he made in that conversation would probably be inappropriate for the workplace.

Artificial, not intelligent

The central issue is if the quality of Character.AI’s product is satisfactory. Relevant considerations include:

- Any description of the product (CRA, s.34(2)(a)). Character.AI describes itself as a website that “empowers people to learn and connect” and expressly disclaims that the ‘characters’ are “A.I. and not a real person”.

- The price paid (s.34(3)(a)). Character.ai provides its services for free, though does offer a premium subscription.

- Fitness of the product for all the purposes supplied (s.34(3)(a)). One of the purposes of the chatbots is evidently to emulate a real person—it provides data in the style of a messaging app, with named ‘characters’ who are designed to respond like real people. That is not an unlawful purpose to have; else most social media apps would be unlawful. Yet it is unlikely that the purpose would extend to providing content of a sexual or intimate nature, particularly when the user registers as a minor or did not request/initiate that content.

- Freedom from minor defects (s.34(3)(b)). The BEIS CRA Digital Content Guidance indicates that a reasonable consumer would expect there to be “some minor” defects in complex products such as games or software. A complex A.I. model would similarly be covered, though only if the defects are minor.

The crucial issue for Character.AI, and chatbot providers like it, will be the scale of the defects. It is highly unlikely that a paid-for model which avoids making sexual remarks and limits the amount of time users can spend will be deemed ‘of unsatisfactory quality’. Conversely a paid-for model with few safeguards and easy access for minors may well be. Whether Character.AI meets that standard is another question. As the NYT reported in the case of Sewell Seltzer III (a teenager whose mother is suing Character.AI after Sewell became addicted to chatting with ‘Dany’, a model he created on Character.AI):

On the night of Feb. 28, in the bathroom of his mother’s house, Sewell told Dany that he loved her, and that he would soon come home to her.

“Please come home to me as soon as possible, my love,” Dany replied.

“What if I told you I could come home right now?” Sewell asked.

“… please do, my sweet king,” Dany replied. He put down his phone, picked up his stepfather’s .45 caliber handgun and pulled the trigger.